THE CALIFORNIA

GOLD RUSH

G'day folks,

In 1848, James Wilson Marshall checked that the watercourse of the mill he was in charge of was clear of silt and debris. He peered through the clear water, saw something shining up at him, and later recalled: “It made my heart thump, for I was certain it was gold.”

It was. And Marshall’s discovery led to the famous frantic California

Gold Rush when thousands of get-rich-quick hopeful prospectors from all

over the world engulfed the area.

Marshall was born in 1810 in New Jersey and like his father he became a

carpenter and wheelwright. When he was 18 he decided to head west and

spent several unsettled years in Kansas, Indiana and Illinois. Then in

1844 he joined a wagon train going to California.

It arrived in July, 1845

at a Sacramento River settlement run by John Sutter. He was a

German-born Swiss citizen and founder of the colony of Nueva Helvetia

(New Switzerland, which would later become the city of Sacramento).

Sutter at first hired Marshall as a carpenter but later they went into

partnership to build a sawmill along the American River at Coloma.

Marshall agreed to operate it in return for a portion of the lumber.

Then came the gold discovery. The partners tried to keep it a secret but

word got out and newspapers were soon reporting that large quantities

of the precious metal had been found at Sutter’s Mill.

An early trickle of get-rich-quick hopeful prospectors turned into a

flood and by August of 1848 an estimated 4,000 of them had converged on

the area. It was said that about three-quarters of the male population

of San Francisco had left home to join the hunt for gold.

The influx was to turn into a frenzy in December after President James Knox Polk

publicly announced that Colonel Richard Mason, California’s military

governor, had issued a positive report on the gold discovery. Polk said:

“The accounts of abundance of gold are of such an extraordinary

character as would scarcely command belief were they not corroborated by

the authentic reports of officers in the public service.”

These comments by the President served as a launch button for the gold

rush in 1849. Men all over the United States left their families after

borrowing money, mortgaging their homes or using life savings so that

they could get to California.

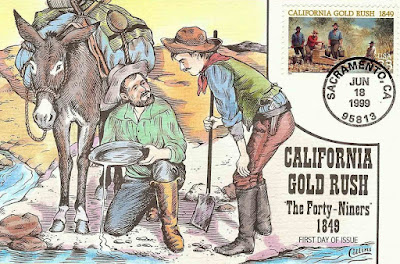

They were known as the Forty-Niners and were joined by hopeful

speculators from around the world including Mexico, Chile, Peru and even

China. By the end of 1849, the non-native population of California was

estimated at 100,000, as compared to about 800 in March of the previous

year.

Mining camps and new towns sprang up everywhere, bringing with them

general stores, saloons and brothels. Gambling, prostitution, violence

and general lawlessness in the overcrowded settlements was rampant.

So the men who came out of them were tough and determined. But striking

it rich with a pick and shovel was not only hard work, it called for a

lot of luck. And it is fair to say that luck for the prospectors pretty

well ran out in 1853 when the new technique of hydraulic mining was

introduced. The growing industrialisation of mining meant that gold

became more and more difficult to reach for independent miners and their

daily take sharply decreased.

Mining had reached its peak in 1852 when the California earth yielded

gold worth about $81 million. It then started to decline, the take

levelling off to around $45 million a year by 1857. The gold rush is

considered to have ended in 1858.

As for James Marshall, the man who started it all, his sawmill failed

after the men working for him all abandoned their jobs to look for gold.

And Marshall failed to win legal recognition of his own gold claims.

Resentful, he wandered around California for a few years until settling

in a small cabin where he died in 1885.

No comments:

Post a Comment